When asked which city best preserves their country’s traditions, Koreans often pick Jeonju, a city in North Jeolla Province that boasts many

hanok, traditional Korean wooden houses. Much like its eclectic versions of

bibimbap, Jeonju offers a delightfully harmonious mix of the well-preserved past and modern culture and innovation.

© Shutterstock

Jeonju’s hanok village is the largest by size in Korea, with more than 700 traditional houses preserved in an area spanning 300,000 square meters. A great place to start a tour is Omokdae, a pavilion atop a steep hill that offers a panoramic view of the entire hanok village. The densely packed tiled roofs give the illusion of surging dark blue waves.

DAWN OF THE JOSEON DYNASTY

Omokdae also holds historical significance. Before Yi Seong-gye became the founding king of the Joseon Dynasty (as King Taejo, r. 1392–1398), he served as a general during the late Goryeo period. In September of 1380, despite being heavily outnumbered, Yi led his troops to a decisive victory against waegu, pirates from Japan whose raids had plagued the Korean peninsula. Before his triumphant return to Seoul, he stopped by Jeonju, the ancestral home of his clan, for a celebratory feast, during which he is said to have sung the poem “Song of the Great Wind,” now written on one of the plaques inside the pavilion.

A strong wind scatters the clouds.

I have returned home in glory after a triumphant victory.

How can we find warriors to defend our country!

Yi’s choice of poem has sparked speculation that he effectively revealed his ambition to overthrow the old dynasty and establish a new one, which he would realize around a decade later. His recital at Omokdae can thus be seen as a harbinger of the 472-year-long Joseon Dynasty.

Along with Bukchon Hanok Village in Seoul, Jeonju Hanok Village is an important area preserving traditional Korean houses. When looking down from Omokdae, its densely packed tiled roofs give the illusion of surging waves.

The pavilion is not the only link between Joseon and Jeonju. At the southern end of the hanok village is Gyeonggijeon. The shrine’s name is derived from gyeonggi, which means “auspicious site.” Yi Seong-gye’s son and second successor, Yi Bang-won (King Taejong, r. 1400–1418), built places to enshrine his father’s portrait in Jeonju and other major cities, including Pyongyang, Kaesong, Yonghung, and Gyeongju.

Visitors donned in traditional Korean clothes at Gyeonggijeon, a shrine reaffirming the roots of the Joseon Dynasty; gyeonggi means “auspicious site.”

Gyeonggijeon is divided into three sections. Jeongjeon is the main hall where a replica of Taejo’s portrait is enshrined. The original is stored in the Royal Portrait Museum behind the hall. Jogyeongmyo, the second section, is an ancestral shrine to the north of Jeongjeon, which was built to enshrine the memorial tablets of Yi Han and his wife. Yi was the founding father of the Jeonju Yi clan and progenitor of Taejo 22 generations back. The third section, the historical archive built to house the Annals of the Joseon Dynasty, lies between the two structures. The Annals contain daily accounts of the dynasty since its founding and constitute the longest historical record of any single dynasty in the world and the only case in which the original volumes remain intact. They have been designated as a national treasure of Korea and are inscribed in the UNESCO Memory of the World Register.

In front of the entrance to Gyeonggijeon is a stele that marks the spot where everyone, regardless of status, had to dismount from their horse. Propping it up are two stone statues of haechi, a legendary creature resembling a lion, that look playful rather than stern, as is characteristic of Joseon stone sculptures. Six large cast iron cauldrons in the courtyard of Jeongjeon held water to extinguish fires. They were also meant to repel fire demons, hoping they would be startled at the sight of their ghastly reflections in the water and flee. In an otherwise solemn space, these whimsical elements are evidence of the wit of Joseon-era Koreans.

A stele in front of the entrance to Gyeonggijeon marks the spot where everyone, regardless of status, had to dismount from their horse.

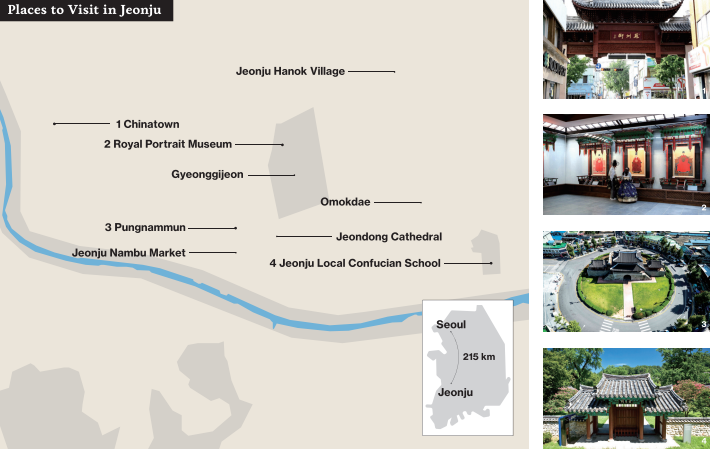

Along with Omokdae, Gyeonggijeon, and the hanok village, other sites also reflect the history, tradition, and stature of Jeonju. These include Jeolla Gamyeong, the provincial governor’s office that oversaw the affairs of the present-day North and South Jeolla provinces as well as Jeju Island during the Joseon Dynasty, and Pungnammun, the south gate and only remnant of Jeonju Fortress that once encircled the city.

LEGACY OF EXCHANGES

People usually associate Jeonju with the Joseon Dynasty and Korean traditions, but it is more than just a city of relics dating back hundreds of years. A closer look reveals a legacy of exchanges with other countries and cultures that have shaped Jeonju’s contemporary identity.

Across from Gyeonggijeon, the Roman-Byzantine style Jeondong Cathedral stands tall. Completed in 1914, it was built on the site of the first Catholic martyrdom in Korea. Interestingly, many laborers who worked on the cathedral’s construction were not, in fact, Korean. According to 100-Year History of Jeondong Cathedral, more than 100 Chinese workers — five carpenters and some 100 stonemasons — built a kiln and baked 650,000 bricks. Their supervisor, Gang Ui-gwan, operated the architectural firm Ssangheungho and is known to have constructed various Catholic structures.

Completed in 1914, Jeondong Cathedral is a Roman-Byzantine style building that is among the largest of early Catholic churches in Asia.

The history of Chinese immigrants to Jeonju dates back to 1899, when the port of Gunsan opened 50 kilometers away. Merchants and laborers seeking to make a living put down roots in Jeonju, which was more advanced in terms of commerce, culture, and administration. Over time, a Chinese community formed that gave rise to the present-day Daga-dong Chinatown. Some of these immigrants were employed in the shipping or farming industries, but around 60 percent worked in the restaurant business or traded fabrics, such as silk and satin.

Acculturation brought on by the Chinese community in a city with a rich tradition had a particularly profound impact on the Korean palate. Chinese cuisine incorporating locally sourced ingredients gained widespread popularity. A case in point is jjajangmyeon, a Korean-Chinese noodle dish with black bean sauce. Taking it a step further, Chinese chefs in Jeonju d mul-jjajangmyeon, a variation using soy sauce to cater to Korean customers who may find black bean sauce too rich and oily. Starch is added to thicken the sauce, which is poured over boiled seafood and flour noodles. The result is a dish akin to assorted seafood noodle soup.

Mul-jjajangmyeon became a huge hit and evolved further, with a spicy version d to suit Koreans’ predilection for heat. Two well-known restaurants in Jeonju carrying on the tradition of mul-jjajangmyeon are Jinmi Banjeom, run by Ryu Yeong-baek, an ethnic Chinese local who is also the principal of Jeonju Chinese Elementary School, and Daebojang, a family business which opened in 1962.

Incidentally, culinary contributions by the Chinese community in Korea are not just seen in Jeonju but the entire country. Humble cellophane noodles, which originated in China, are a good example; they have become a key ingredient for bulgogi (barbequed beef), galbitang (short rib soup), japchae (stir-fried noodles with vegetables), and even sundae (Korean blood sausage). Jeonju has readily embraced numerous cultural influences; the city today is the sum of those interactions.

BIBIMBAP INNOVATION

The city’s most famous dish, Jeonju bibimbap, is known for its aesthetically pleasing colors and sumptuous taste. Local chefs have continuously reinvented it, and the dish remains widely enjoyed today.

Jeonju bibimbap, a local specialty of the city, has become a dish representing Korea’s culinary tradition. There are over 30 varieties whose ingredients differ slightly depending on the season.

Jeonju’s oldest bibimbap restaurant is Han Kook Jib, which opened in 1951. In the early days, the business was called Hankook Tteokjip, and the owners sold rice cakes and jeonggwa, a traditional Korean confection. They later added tteokguk, rice cake soup, to the menu, but since the dish was mainly eaten in winter, they concocted baengbaengdori, which could be sold year-round.

Baengbaengdori is the Jeonju name for bibimbap and describes the way the rice and various ingredients are mixed by stirring them in a circular motion with a spoon or rice paddle. It was once customary to first mix the cooked rice and assorted vegetables in a huge bowl before filling customers’ individual bowls. The late scholar Cho Byung-hee, an expert in Jeonju history, described baengbaengdori in his 1988 essay “Nambak Market in the 1920s.”

“When you go to a restaurant, you will see a worker with a sturdy build supporting a large brass bowl with one hand and adeptly mixing the bibimbap with two spoons held firmly in the other. They will hum a tune when in the mood, spin the bowl around in the air, then catch it with their hand. This kind of skill can only be witnessed at Nambakjang.”

Nambakjang, short for Nammunbak Sijang, was the market outside the southern gate. It is now called Jeonju Nambu Market and impressive during the day, but the night market is the main attraction for tourists. Restaurants specializing in baengbaengdori are within a short radius of the market. They include Han Kook Jib, which invented an upscale version of the dish featuring bean sprouts, bracken fern, zucchini, shiitake, seasonal greens, aster, and cauliflower mushrooms as well as the highlight, beef tartare. The creation has inspired countless other bibimbap restaurants in Jeonju to invent their own interpretations.

While Ha Suk-yeong Gamasot Bibimbap, formerly known as Jungang Hoegwan, serves its bibimbap in a hot stone pot and adds nutritious ingredients, such as ginkgo nuts, chestnuts, and jujube, Seongmidang’s twist includes pre-frying the rice before serving it. Bibimbap Alley, near Nambu Market, has long been a popular spot among Jeonju citizens as well as a must-visit destination for tourists. The location, which began to flourish in the 1960s, has played host to the Jeonju Bibimbap Festival every fall since 2007.

The 25th JEONJU International Film Festival in May was celebrated across the city, including at Film Street, a 10–15 minute stroll from Jeonju Hanok Village. A total of 232 films from 43 countries were screened over ten days.

TRADITIONS AND INCLUSIVITY

Jeonju is a city where you can encounter traces of Korea’s past and various facets of its present, from the foundation of the Joseon Dynasty and enriching exchanges with other countries to today’s tireless efforts to innovate and evolve while also upholding tradition.

Jeonju has a relaxed pace and offers a harmonious blend of nature and culture. In 2010, it became the first large Korean city with a population of over 500,000 to earn a designation as a Slow City by Cittaslow International. Two years later, Jeonju was named the fourth UNESCO Creative City of Gastronomy in recognition of its efforts to protect traditional food culture and develop the gastronomy sector. Jeonju is a travel destination that reminds us why we should continue to reinterpret and build on history and traditions based on inclusivity, rather than simply reproducing them.

All photos © Korea Tourism Organization